|

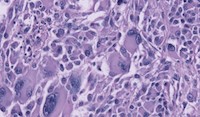

| Glioblastoma--Courtesy of Virginia Tech |

The chemotherapy drug temozolomide (TMZ) can be quite effective in patients with glioblastoma, a deadly form of brain cancer, but virtually all patients eventually become resistant to it. Now scientists from the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute believe they have discovered a way to resensitize glioblastoma cells to the treatment--and they're turning to pet dogs that have developed the same type of brain tumor to help prove it.

The scientists discovered that glioblastoma cells have abnormally high levels of a protein called connexin 43. "The higher the connexin 43 levels, the quicker the cancer cells become resistant to TMZ," said Robert Gourdie, director of the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute's Center for Heart and Regenerative Medicine Research, in a press release. Gourdie was doing heart research when he observed that connexin 43 facilitates cell signaling, but that the process can become overactive in cells that are damaged by disease.

So Gourdie and his team developed a peptide called aCT1 to inhibit that overactivity. In studies with human glioblastoma cells, the scientists discovered that combining aCT1 with TMZ restored the cancer's ability to respond to treatment. They reported their insights about how aCT1 might lessen resistance to TMZ in a recent edition of the journal Cancer Research.

The researchers will soon open a study of the combo treatment in dogs with glioblastoma, in collaboration with the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine. The owners of dogs who are enrolled will receive all imaging, the experimental treatment and standard drugs traditionally given to treat the disease free of charge, according to a Virginia Tech spokeswoman. After the data is analyzed, a human clinical trial will begin. The researchers have formed a company, FirstString Research, to further the development of the treatment.

Glioblastoma represents half of all brain cancers, and fewer than 20% of patients survive for 5 years beyond their diagnosis, according to Virginia Tech. The prevalence of the disease is roughly the same in dogs, who also face a poor prognosis.

There is a growing interest in recruiting pet dogs with cancer for clinical trials that could result in better treatments for both people and dogs--and glioblastoma is one of the major targets of that research. In February, the scientists behind another technique developed at Virginia Tech called nonthermal irreversible electroporation won a grant from the National Cancer Institute after they published a paper showing they were able to extend the life of a dog with glioblastoma by 5 months. The technique, delivered by electrodes placed in the brain, uses electrical pulses to permeate the membranes of cancer cells and cause them to die. The grant allowed the researchers to further develop the treatment for use in people.

- access the Virginia Tech press release here

- here's an abstract of the Cancer Research article