|

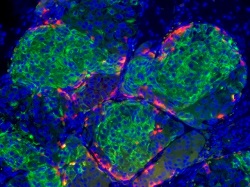

| Insulin-producing beta cells (green) generated from embryonic stem cells--Courtesy of the Melton Lab/Harvard University |

The self-regulation of insulin delivery is a long-sought goal in the field, spurring the development of closed-loop systems and an artificial pancreas for diabetics. But some researchers are aiming smaller, looking at a way to create stem cells en masse that can produce insulin in response to blood sugar levels.

Harvard researchers have developed a method to generate "hundreds of millions" of pancreatic beta cells from stem cells that secrete insulin the way an adult beta cell would in response to changes in glucose levels. Previously, stem cell-derived pancreatic cells have lacked some of the functional insulin-producing characteristics, but this new model expresses the markers found in mature beta cells, contains calcium ions that respond to glucose and packs the insulin away in granules that release it when needed, according to the abstract in the journal Cell.

"We're thinking about it as sort of like a teabag, where the tea stays inside, and the water goes in and then the dissolved tea comes out," lead author Doug Melton told NPR. "And so, if you think about a teabag analogy, we would put our cells inside this teabag."

While advances like this continue to push diabetes treatments further from the back end, work on the artificial pancreas trundles toward regulation. Just this week, Medtronic ($MDT) enrolled the first patients into a study of its Predictive Low Glucose Management technology that could be a step in the right direction. Other companies like Johnson & Johnson ($JNJ) and DexCom ($DXCM) are in the race, as well.

And last year, researchers from NC State, UNC and MIT developed networks of nanoparticles that could be used as "smart" insulin delivery instruments. These types of advances, though, remain in the very early stages.

"It's a huge landmark paper," University of Illinois bioengineer Jose Olberholzer told NPR regarding Melton's work at Harvard. "I would say it's bigger than the discovery of insulin. The discovery of insulin was important and certainly saved millions of people, but it just allowed patients to survive but not really have a normal life. The finding of Doug Melton would really allow to offer them really something that I would call a functional cure. You know, they really wouldn't feel anymore being diabetic if they got a transplant with those kind of cells."

- here's the abstract

- and here's the NPR report

Special Report: The race for the artificial pancreas