|

| UPenn's Jason Burdick |

In a study published in the journal Nature Materials, University of Pennsylvania scientists describe a hydrogel they developed that is designed to be applied directly to the heart muscle to reduce continuing damage after a heart attack.

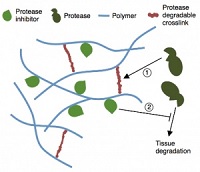

The injectable hydrogel, consisting of a scaffold of natural sugars, holds enzyme inhibitors within its network. After a heart attack, the heart releases enzymes that can cause the muscle to break down, weakening the organ and causing it to enlarge. But when the hydrogel is injected into the heart, these enzymes instead break down the hydrogel, which releases the inhibitors, rendering the enzymes ineffective, according to a university report.

The targeted hydrogel is an important advance in this type of treatment, as patients are often administered these inhibitors orally or intravenously, which can be less efficacious, as they may or may not reach the heart, accumulating in other parts of the body, leading to a host of other issues.

|

| Hydrogel loaded with inhibitors for use after a heart attack--Courtesy of UPenn |

The team tested the gel both in vitro and in pigs, and the experiments showed that the hydrogel helped retain the inhibitors over time, allowing only about 20% of them to be released in a few weeks, as opposed to about 80% over the course of a few days without the gel structure.

"We used a microdialysis technique to show that, after a heart attack, local enzyme levels go way up, but when the inhibitor molecules are delivered via the gel, we see the activity level of this enzyme go down," co-author Brendan Purcell said in a university statement. "Over the next 28 days, we also used imaging techniques to show thicker cardiac walls and less expansion and dilation of the ventricle. And, as a result, we see better performance in the heart using clinical measurements like ejection fraction, the amount of blood the heart is pumping."

The National Institutes of Health and the Veterans' Affairs Health Administration helped fund the study.

"What's appealing about our approach is that we are trying to intervene early," lead researcher Jason Burdick said in a statement. "We want to attenuate the remodeling process to limit these negative outcomes and prevent the onset of congestive heart failure."

- here's the UPenn report

- and here's the abstract