|

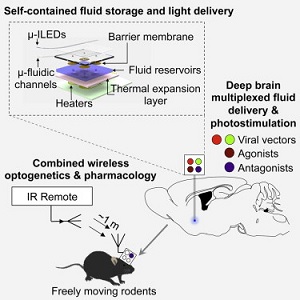

| Neural probe using optogenetics and therapeutics to target areas of the brain--Courtesy of Washington U. and U. of Illinois |

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have overcome a common problem in drug delivery to the brain, which is to get the therapies to target certain brain circuits without accidentally affecting other parts of the brain or body.

To target the brain cells, the researchers used a small wireless implant loaded with drugs that could be activated at the push of a remote button. Preliminary tests in mice showed that a drug delivered via the device to a mouse's brain stimulated neurons that dictate movement, and the mice would then walk in circles. This demonstrates that the device can target specific areas of the brain with minimal side effects.

Combined with the drugs, the device makes use of cellular signalling in the form of optogenetics, using flashes of light to activate the parts of the brain, controlling the delivery of fluid therapeutics to the area.

And the device itself, only the width of a human hair, appears to be safe in an area as sensitive as the brain. It is an ultrathin, soft microfluidic light-emitting diode, according to the abstract published in the journal Cell.

"The device embeds microfluid channels and microscale pumps, but is soft like brain tissue and can remain in the brain and function for a long time without causing inflammation or neural damage," lead author Jae-Woong Jeong of the U. of Illinois said in a statement.

More time and effort is spent studying drug delivery devices these days, particularly for the central nervous system. In June, researchers at Purdue University implanted a device in the spinal cords of mice with compression injuries to deliver the corticosteroid dexamethasone for weeks at a time.

These types of minimally invasive brain probes offer to give drug delivery a leg up because they are able to bypass the blood-brain barrier, which has long been a daunting hurdle in the field.

- here's the Cell abstract

- and here's a report from BioScience Technology