|

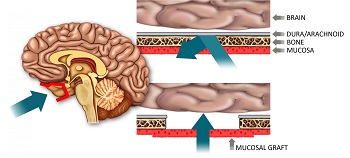

| Depiction of a mucosal graft allowing access to the brain--Courtesy of Harvard |

To treat many neurological diseases, drugs must first pass the blood-brain barrier. But that barrier has formed around the brain to block dangerous substances and, in turn, it thwarts about 98% of drugs, according to a group of Boston scientists. That team has since developed a technique to make crossing the blood-brain barrier less of a hindrance.

The researchers from Massacusetts Eye and Ear at Harvard University and Boston University have developed a nasal mucosal grafting method by which they could deliver a known Parkinson's disease treatment to the brain. The treatment, glial derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), normally can't pass the blood-brain barrier and the standard for delivering it remains a direct injection into the brain, which is not ideal from either a patient's or physician's point of view. But the drug has been shown preclinically to delay or reverse Parkinson's progression, according to a press release.

|

| Dr. Benjamin Bleier |

A surgeon makes a hole in the base of the skull through the nose, a technique commonly used to access the brain endoscopically. But with the new method, the surgeon immediately rebuilds the hole permanently with a small piece of mucosal lining, which is many times more permeable than the blood-brain barrier on the inside of the skull. This creates what the team calls a "screen door" to allow drugs access to the brain.

Currently, they've tested the technique on mice with Parkinson's disease, but the study's authors claim this method could be used to treat an array of neurological disorders. Back in 2013, the researchers published a proof of principle study using a skull from a donor mouse, as opposed to in vivo.

"We are developing a platform that may eventually be used to deliver a variety of drugs to the brain," Mass. Eye and Ear's Benjamin Bleier said in a statement. "Although we are currently looking at neurodegenerative disease, there is potential for the technology to be expanded to psychiatric diseases, chronic pain, seizure disorders and many other conditions affecting the brain and nervous system down the road."

The team, which picked up funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, published the study in the journal Neurosurgery.

- here's the release